The New Reality of Student Learning

Artificial intelligence adoption among students has moved from novelty to norm faster than any previous educational technology. By 2025, approximately 92% of university students report using AI tools regularly, up from 66% just one year prior. Nearly nine in ten students now acknowledge using generative AI tools for tests and assessments.

These numbers should command the attention of every university leader. Yet institutional readiness lags far behind student adoption. Only 9% of chief technology officers believe higher education is prepared for AI's rise, and 80% of students report that their university's integration of AI tools does not meet their expectations. Three-quarters of higher education CTOs now view AI as a significant risk to academic integrity, while 59% of university leaders say cheating has increased in the past year.

This is not a question of whether to engage with AI, but how to lead the transition strategically. The students entering your classrooms today will graduate into a workforce where AI fluency is not optional. The institutions that thrive will be those that understand how AI is reshaping study habits and respond with principled, adaptive policies.

How Generative AI Functions in Academic Contexts

University leaders need not become technical experts, but functional literacy in how these tools operate is essential for sound decision-making.

Generative AI systems like ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot, and Grammarly work by analyzing massive datasets of text to recognize patterns in language, structure, and meaning. When a student enters a prompt, the system generates contextually appropriate responses based on statistical predictions about what should come next. The result can be remarkably coherent text, code, summaries, or explanations produced in seconds.

The scale of adoption is striking. ChatGPT remains the dominant tool, used by 66% of student respondents in global surveys, followed by Grammarly and Microsoft Copilot at 25% each. On average, students now use 2.1 AI tools for their coursework.

How are students actually deploying these tools? The most common use cases include creating first drafts and outlines, breaking down complex concepts step by step, summarizing readings and research literature, generating practice problems and study guides, and getting real-time tutoring on difficult material. One student described the appeal simply: rather than spending hours searching through a textbook, AI can pull together the most relevant information in seconds.

The central tension institutions must navigate is the distinction between AI as a cognitive partner that enhances learning and AI as a work replacement that undermines it. This distinction should inform every policy decision.

The Case for AI Integration

The benefits of thoughtful AI integration are substantial and supported by growing evidence.

Personalized learning at scale. AI tools can adapt to individual student pace and knowledge gaps in ways that traditional instruction cannot match. Research indicates that students using AI-enhanced learning environments score up to 54% higher on standardized assessments. As one Stanford professor observed, AI has the potential to support a single teacher in generating 35 unique learning conversations with each student, something impossible through traditional methods alone.

Democratizing access. AI tutoring can narrow the gap between students who can afford private tutors and those who cannot. OpenAI has explicitly positioned its educational features as tools to close this equity gap. For first-generation students and those at under-resourced institutions, AI offers a form of academic support previously available only to the privileged.

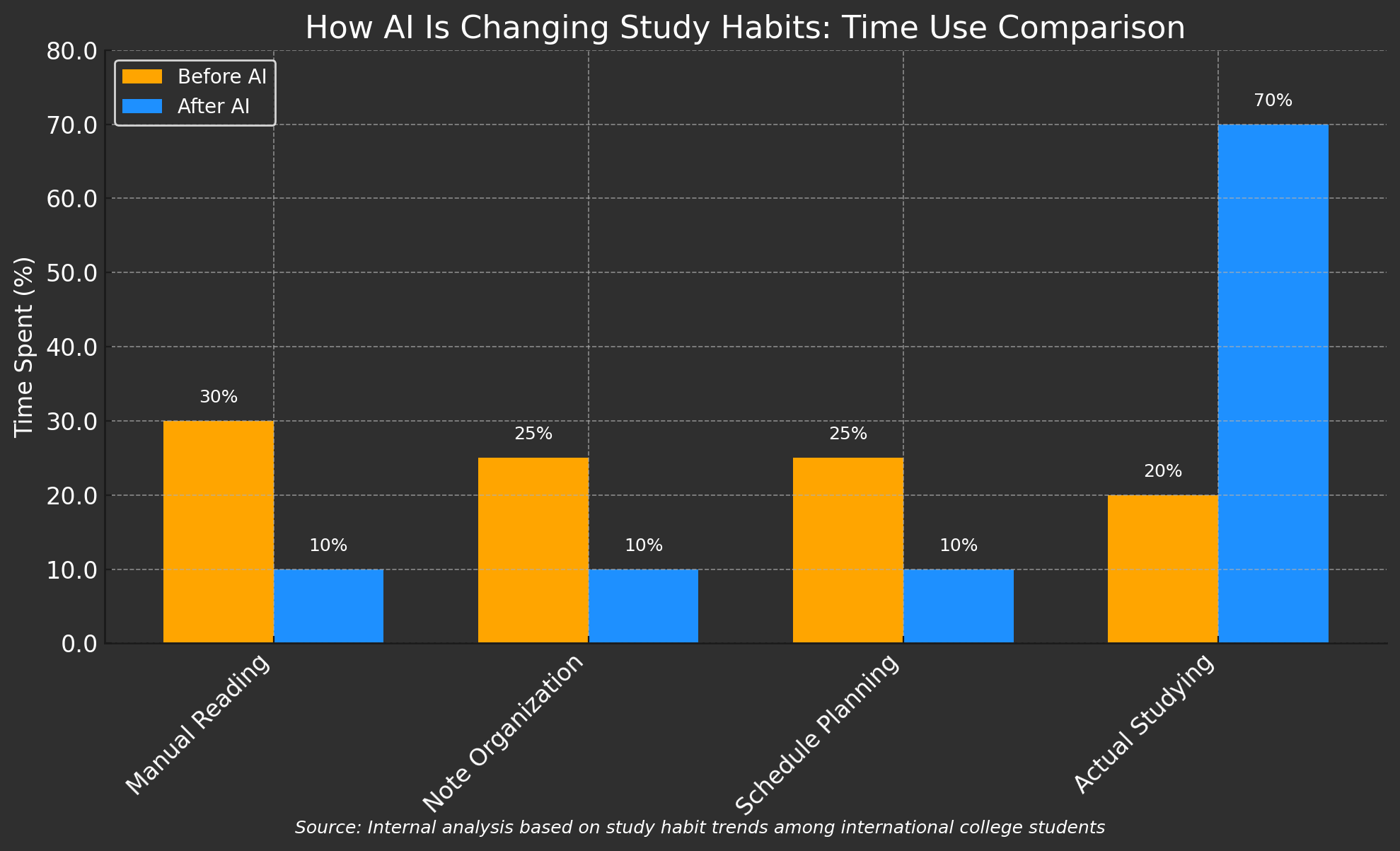

Efficiency gains. Studies have found significant reductions in study hours alongside increases in GPA when students use AI strategically. On the administrative side, AI tools can reduce the cost of education administration by 20 to 30 percent. Faculty can redirect time from repetitive tasks toward the high-value mentorship that defines excellent teaching.

Workforce preparation. By 2030, approximately 70% of job skills are expected to change, primarily due to AI. Students recognize this reality. Survey data shows that 94% of graduates who received AI training in college report career benefits, including greater job stability, faster promotions, and higher starting salaries. When 65% of higher education students believe they know more about AI than their instructors, and 45% wish their professors taught AI skills in relevant courses, the message is clear: students want preparation, not protection from the tools that will define their professional lives.

Risks and Institutional Concerns

The case for caution is equally compelling. University leaders must weigh genuine risks that could undermine educational quality and institutional mission.

Academic integrity challenges. The integrity concerns are not hypothetical. A majority of university leaders report increases in cheating, and the tools designed to detect AI-generated content remain unreliable. Evaluations of 14 AI detection tools found accuracy rates below 80%, with some studies showing significant bias against non-native English speakers. Detection-based enforcement strategies face serious limitations.

Skill atrophy and over-reliance. Nearly half of students surveyed express concern about the accuracy of AI-generated content, yet many continue to rely on it heavily. The deeper risk is cognitive: when AI performs the thinking rather than supporting it, students may fail to develop the critical reasoning skills that higher education exists to cultivate. As Professor Martin West of Harvard has noted, some uses of generative AI can undermine learning, particularly when tools do the cognitive work for students rather than supporting their development.

Knowledge and literacy gaps. Paradoxically, despite widespread use, students report feeling unprepared. Fifty-eight percent say they lack sufficient AI knowledge and skills, and 48% feel inadequately prepared for an AI-enabled workforce. Only 5% of students are fully aware of their institution's AI guidelines. Students are using tools they do not fully understand, governed by policies they have not read.

Data privacy and security. Information shared with generative AI tools using default settings is not private. Students and faculty may inadvertently expose personal information, confidential research, or proprietary institutional data. Compliance with FERPA, GDPR, and institutional data policies requires careful attention to which tools are approved and how they are configured.

Equity considerations. Access to premium AI tools remains uneven across student populations. AI systems can perpetuate or amplify existing biases in their training data. And the faculty development gap is significant: 68% of urban teachers report receiving no AI training since joining their institutions.

Governance Frameworks and Responsible Use

Institutional policy on AI use is evolving rapidly, with no single model dominating. The most effective approaches share common elements: clarity, flexibility, and alignment with educational mission.

The policy landscape. Approaches vary widely across peer institutions. Some prohibit AI use entirely for coursework. Others permit it with disclosure and citation requirements. A growing number are designing curricula that integrate AI as a learning tool. UNC-Chapel Hill now requires all undergraduate course syllabi to include an explicit AI use policy, with faculty encouraged to select from sample statements ranging from prohibition to full acceptance depending on course context.

Three emerging models. The prohibition model forbids AI tools for coursework, protecting foundational skill development but growing increasingly difficult to enforce and disconnected from workplace realities. The conditional permission model allows AI use with transparency requirements: students must disclose which tools they used, how they used them, and be prepared to explain their work verbally. This approach is gaining traction at institutions including Cornell, Columbia, and Carnegie Mellon. The full integration model embeds AI into course design and assessment, with assignments structured around AI collaboration rather than despite it. This approach shifts evaluation toward synthesis, judgment, and application rather than content generation.

Implementation essentials. Whatever model an institution adopts, effective implementation requires several elements. Clear communication must occur at course, department, and institutional levels. Faculty need development and support, not mandates; currently only 45% of instructors actively use AI, and 82% cite academic integrity as their top concern. Citation standards should align with APA, MLA, and disciplinary norms, with many educators now requiring students to submit conversation transcripts or reflective statements explaining their AI use. Students need mechanisms to ask clarifying questions without penalty.

Sample policy elements. Leading institutions are incorporating specific provisions: defining what constitutes generative AI in their context, specifying whether restrictions apply at the course or assignment level, requiring students to be prepared to verbally explain submitted work, and situating consequences for undisclosed AI use within existing integrity frameworks rather than creating parallel enforcement systems.

The goal, as one teaching center articulates it, is to view AI as a partner rather than a villain, creating policies that reflect the reality of an AI-augmented world while maintaining the intellectual rigor that defines higher education.

Preparing for What Comes Next

The pace of change will accelerate. University leaders should plan for a five-year horizon in which AI capabilities expand dramatically and competitive pressures intensify.

Market trajectory. The AI in education market is projected to grow from approximately $7 billion in 2025 to over $40 billion by 2030. Asia-Pacific nations are leading adoption with aggressive government mandates. South Korea has invested roughly $830 million in AI-powered digital textbooks with real-time feedback and adaptive learning. China has made AI a required subject in all primary and secondary schools. European initiatives are establishing AI literacy requirements across educational systems. American institutions that delay strategic engagement risk falling behind international competitors.

Near-term developments. Several trends warrant attention. Agentic AI systems that complete multi-step tasks autonomously, conducting research, analyzing data, and producing drafts, will move from experimental to mainstream. Embodied AI in the form of intelligent robotics will begin entering library, laboratory, and administrative functions. Assessment strategies will shift from detection and punishment toward designing evaluations that measure skills AI cannot easily replicate. The most forward-thinking institutions are already redesigning assignments around critical thinking, ethical judgment, and creative synthesis.

Strategic questions for planning. University leadership teams should be asking: What AI literacy competencies should every graduate possess regardless of major? How will AI reshape space utilization, staffing models, and administrative structures? Which programs and disciplines face the greatest disruption, and how should curricula adapt? What equity commitments must accompany AI adoption to avoid widening access gaps?

Faculty and staff implications. Investment in professional development is non-negotiable. Faculty need training, resources, and time to adapt their teaching. The K-12 sector is moving quickly: 74% of districts plan to train teachers on AI by Fall 2025. Higher education should match or exceed this pace. Faculty concerns about integrity are legitimate and must be addressed with support rather than dismissed as resistance to change.

A Leadership Agenda

AI has already transformed how students study. The 92% adoption rate is not a trend to monitor but a reality to manage. The benefits of personalization, expanded access, and efficiency gains are real, as are the risks to integrity, skill development, and equity.

The path forward requires neither uncritical embrace nor defensive prohibition. It requires the same strategic seriousness that university leaders bring to any major institutional challenge.

The immediate agenda should include auditing current institutional readiness and policy gaps, investing in faculty development and student AI literacy programs, convening cross-functional working groups spanning academic affairs, information technology, student services, and legal counsel, establishing clear and adaptable policies that can evolve alongside the technology, and positioning your institution as a thoughtful leader in the AI-augmented future of learning.

Students are not waiting for permission to use these tools. They are using them now, often without guidance, frequently without understanding their limitations, and sometimes in ways that undermine their own learning. The question facing university leadership is not whether AI will reshape higher education. It is whether your institution will shape that transformation or be shaped by it.

The institutions that thrive will treat AI not as a threat to be contained but as an inflection point requiring vision, principle, and sustained attention. That work begins now.