AI in higher education has moved from experiment to expectation. Students now use AI tools as routinely as word processors, and adoption has accelerated faster than most institutions anticipated.

For university leadership, this shift requires immediate attention. AI adoption is no longer a question of if, but how. Effective policy, pedagogy, and faculty development depend on understanding how students actually use AI, how widespread adoption has become, where academic integrity challenges arise, and how student skills and faculty roles are changing as a result.

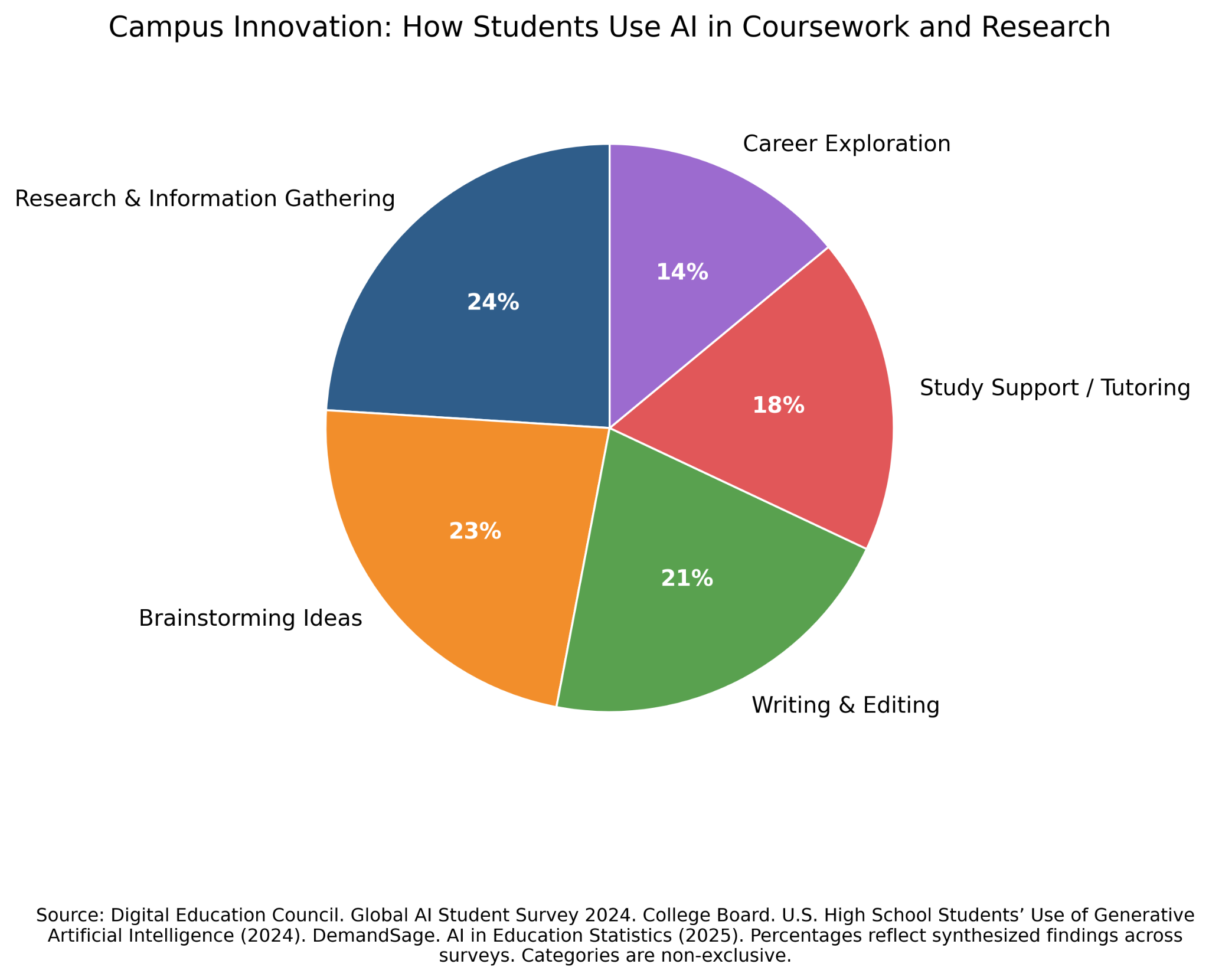

How Students Use AI in Education

Students have integrated AI across nearly every stage of academic work. Common uses include information search, grammar checking, document summarization, and creating . Many also rely on AI to explain complex concepts, brainstorm ideas, solve math problems, and generate code.

ChatGPT remains the dominant tool, followed by Grammarly and Microsoft Copilot. U.S. students average , indicating task-specific tool selection rather than reliance on a single platform.

Usage varies by discipline. STEM students primarily use AI for problem-solving and code generation. Business students apply it to report drafting and analysis. Humanities students rely on AI for research support and editing.

Importantly, students cite efficiency and explanation as primary motivations. A found that 84% of students still prefer human help when struggling academically. AI functions as a supplement, not a replacement, for instructional support.

The Numbers: How Many Students Use AI

Adoption rates are high and rising. In the U.S., 65% of college students use AI chatbots weekly. Among online learners, 60% report using AI for assignments, . Teen use of ChatGPT for schoolwork doubled from 13% in 2023 to 26% in 2024. Usage remains highest among business and STEM majors.

Globally, student AI use rose from 66% in 2024 to . The share of students using generative AI for assessments increased from 53% to 88% in one year. In parallel, 89% of U.S. higher education leaders estimate that at least half of their students use AI for coursework.

Despite widespread adoption, preparedness remains limited. Fifty-eight percent of students report insufficient AI knowledge, and 48% feel unprepared for an AI-enabled workforce. Eighty percent say does not meet expectations.

Policy awareness is inconsistent. Fifty-eight percent of U.S. students report that their program has an AI policy, while 28% say . As of spring 2025, only 28% of U.S. institutions have a , with another 32% still developing one.

AI and Essay Writing: Where the Line Gets Blurry

Student views on AI-related misconduct remain divided. Fifty-four percent of U.S. students consider AI use on coursework cheating or plagiarism, while 21% do not. Over half report they would .

Enforcement poses challenges. AI detection tools show significant limitations, including disproportionate flagging of . Stanford researchers found that more than half of TOEFL essays were incorrectly classified as AI-generated. Even low false-positive rates could affect .

Faculty reporting of AI misuse has increased, with 63% reporting incidents in 2023-24. Investigations and appeals place additional strain on instructional time.

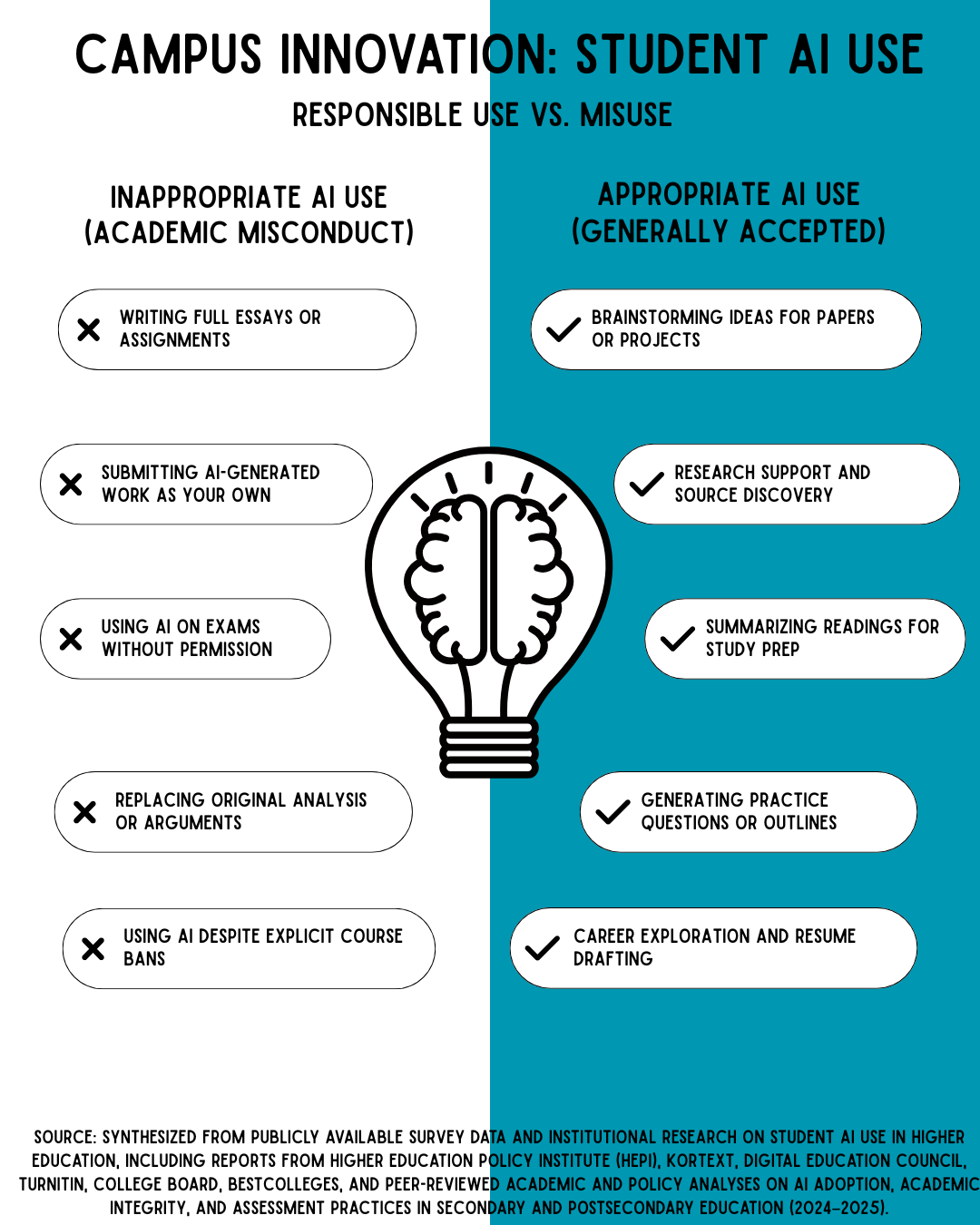

AI use exists on a spectrum:

Brainstorming and outlining are broadly accepted

Editing and grammar assistance are generally permitted

First-draft generation remains contested

Submitting AI-generated work as original constitutes clear misconduct

In response, some institutions are redesigning assessments to emphasize oral presentations, in-class work, and iterative drafts that document learning processes rather than outputs alone.

The Institutional Response

Institutional responses remain uneven. Only 20% of U.S. colleges have published governing teaching and research, although 57% now list AI as a .

Existing policies typically address data restrictions, citation requirements, instructor-level discretion, and misconduct consequences. In the absence of centralized guidance, faculty decisions vary across departments and course sections.

Internationally, responses have advanced more quickly:

Australia's emphasizes responsible use and student privacy

The mandates AI literacy and classifies education as requiring additional safeguards

UK guidance emphasizes

South Korea has invested heavily in AI-powered digital textbooks

Across jurisdictions, the common approach balances innovation with enforceable guardrails.

The Risks Institutions Must Address

AI adoption introduces several risks requiring direct institutional action.

Academic integrity remains the most visible concern. AI enables misconduct that traditional detection tools cannot reliably identify and may reduce student engagement with .

Data privacy and security risks are increasing. Administrative concern over data privacy rose from 50% to . FERPA compliance becomes more complex as AI systems collect and analyze student data.

Algorithmic bias presents equity challenges. AI detectors have demonstrated bias against , and predictive systems may underestimate outcomes for underrepresented students.

Cognitive skill erosion also warrants attention. Overreliance on AI may weaken and analytical reasoning, particularly when outputs are accepted without verification.

Equity gaps may widen as access to advanced AI tools remains uneven across institutions and student populations.

AI and Student Skill Development

AI is reshaping skill development. Skills under pressure include independent research, original writing, and deep analytical reasoning. When AI performs early synthesis and composition, students may not develop these capabilities fully.

At the same time, new competencies are emerging. Students must learn to frame effective prompts, evaluate AI outputs, verify information, and integrate AI into workflows responsibly.

Labor market demand reflects this shift. The World Economic Forum projects that nearly 40% of within five years, with creative thinking ranked as the . Employers increasingly expect graduates who can use AI effectively while exercising human judgment.

Evolving Faculty Roles

Faculty roles are shifting from information delivery toward facilitation of evaluation, synthesis, and application. Assessment design now requires priority attention.

Process-based and performance-based assessments, including oral evaluations and in-class work, offer . Some instructors now require AI use documentation and reflective analysis.

Faculty readiness remains uneven. While 61% of faculty report using AI in teaching, most do so minimally, and .

Institutions must provide clear guidelines, targeted professional development focused on pedagogy, and protected time for curriculum redesign.

Recommendations for University Leadership

Policy: Establish institution-wide AI guidelines with course-level flexibility. Create transparent misconduct processes and robust data privacy protections.

Faculty support: Invest in applied professional development and provide time and structures for assessment redesign.

Student preparation: Integrate AI literacy across curricula alongside academic integrity expectations.

Governance: Create representative AI governance bodies and evaluate tools for bias, privacy, and pedagogical fit.

Conclusion

AI is already embedded in student learning. The challenge for institutions is not adoption, but direction.

Institutions that align policy, pedagogy, and faculty support with actual student AI use will graduate students prepared for AI-integrated work environments. Those that delay risk widening gaps between practice and preparedness.

Leadership decisions made now will shape whether AI strengthens higher education or undermines it.

Smaller Study Sets, Better Results? How New Data Shapes College Study Habits

Smaller Study Sets, Better Results? How New Data Shapes College Study Habits

Social Media Screening and Information Security Risks in Hiring and Admissions

Social Media Screening and Information Security Risks in Hiring and Admissions

The Hidden Economy of International Students: Who Really Profits From Global Education?

The Hidden Economy of International Students: Who Really Profits From Global Education?

How University Leadership Can Assess the Strategic Use of Advanced Large Language Models

How University Leadership Can Assess the Strategic Use of Advanced Large Language Models

The Cheapest Cities for International Students

The Cheapest Cities for International Students